Peck devoted himself to organizing work and journalism on behalf of pacifist and social justice causes. During World War II, he was a conscientious objector and an anti-war activist, and consequently spent three years in jail. While in prison, he helped start a work strike that eventually led to the desegregation of the mess hall.

Peck was released from prison in 1945, and immediately joined protests to grant amnesty to WWII conscientious objectors. He worked with the Amnesty Committee in organizing protests and writing press releases. On May 11, 1946, he joined the largest amnesty protest, 100 people at the White House while prisoners carried out hunger strikes. The activists outside the White House wore black-and-white prison outfits to represent those remaining in prison. In June 1947, the group staged a "mock funeral" in front of the White House. Pallbearers dressed in formal attire and carried a coffin marked "justice."

In the late 1940s, Peck became increasingly involved in issues of racial justice, joining the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) as a volunteer. In 1961, Peck and 15 other volunteers traveled South in the Freedom Rides. He was arrested on May 10, 1961 in Winnsboro, South Carolina, for sitting in “an integrated fashion” at a lunch counter. On May 14, he was on the second Trailways bus leaving Atlanta, Georgia for Birmingham, Alabama. The first bus, a Greyhound, left an hour earlier and was burned in a firebombing in Anniston, Alabama. The Trailways bus pulled in at the terminal in Anniston and eight Klansmen boarded and assaulted the Freedom Riders.

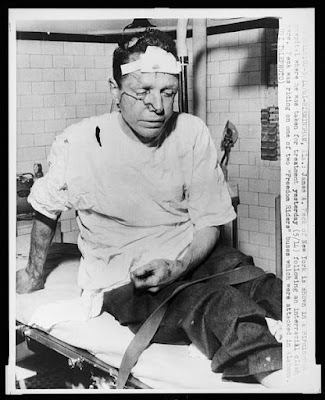

Later, in Birmingham, Peck was one of the first to exit the bus, into a crowd of Klansmen who, with the organizational help of Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner, were waiting for the Freedom Riders. As described by a CBS reporter at the time:

"Toughs grabbed the passengers into alleys and corridors, pounding them with pipes, with key rings, and with fists. One passenger was knocked down at my feet by twelve of the hoodlums, and his face was beaten and kicked until it was a bloody pulp. That was Jim Peck's face."

Peck was severely beaten and needed 53 stitches to his head. It took more than an hour for Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth to find an ambulance willing to take Peck to the all-white Carraway Methodist Hospital, where staff refused to treat him. He was later treated at Jefferson Hillman Hospital.

Peck was now recognized as a white civil rights hero. He traveled around the nation representing CORE in speeches, and gained even more attention for the Movement on June 5, when he confronted President Truman about his recent remarks denouncing the Freedom Riders, making Truman seem behind the times in racial justice. At Peck's suggestion, a Route 40 Freedom Ride project was launched by CORE in December 1961, resulting in half the restaurants desegregating along Route 40 in Baltimore. He was one of the main leaders for the Project Baltimore campaign, which led to more restaurants desegregating. And that summer, he was one of the leaders for the Freedom Highways campaign, which sought to integrate highway restaurants in North Carolina.

Following the Freedom Rides, Peck became good friends with William Lewis Moore, a white civil rights worker who became a martyr for the movement after he was shot and killed in the south during his solo Freedom March in 1963. When Moore was killed, Peck delivered the eulogy at his funeral, and then gave the opening speech on May 19, when several dozen activists continued the march from where Moore was shot down. After the walkers were arrested and taken to jail, Peck and others marched to the jail singing Freedom songs.

On August 2, 1963, Peck was one of 30 people arrested for performing a sit-down in the street, while protesting the discriminatory state policies for the construction of the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. On October 20, he spoke about the racist policies in front of 700 demonstrators at a New York City rally. On August 28, 1963, Peck represented CORE at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He then traveled to Bowie, Maryland, to picket the discriminatory housing policies. On April 22, 1964, Peck was one of the leaders for CORE's campaign at the opening day of New York's World Fair, protesting the discriminatory policies held by most companies sponsoring the Fair. More than 300 demonstrators were arrested on the Fair's opening day, including Peck, James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, and Michael Harrington.

In March 1965, Peck represented CORE at the march from Selma to Montgomery. He spoke as a CORE representative that day. When Peck returned home after the march, he personally funded Martin Luther King's campaigns, especially his 1968 Poor People's Campaign. When Dr. King was assassinated in April 1968, Peck honored him by traveling to Memphis on April 8 to join 40,000 other demonstrators in marching in support of the Memphis Sanitation strike that Dr. King had supported prior to his death. After the Memphis March, he traveled to Atlanta for Dr. King's funeral, which concluded with 50,000 demonstrators marching over four miles. In May 1969, he joined Coretta King and Ralph Abernathy in Charleston, South Carolina, to support black nurses on strike.

In 1975, Gary Thomas Rowe Jr. testified that he was a paid FBI informant in the Klan, and that on May 14, 1961 the KKK had been given 15 to 20 minutes without interference by the police. Peck filed a lawsuit against the FBI in 1976, seeking $100,000 in damages. In 1983, he was awarded $25,000, and by this time was paralyzed on one side after a stroke.

James Peck continued civil rights activism into the 1970s, until his stroke. By 1985, he had moved into a nursing home in Minneapolis, where he died on July 12, 1993, at age 78.

Following the Freedom Rides, Peck became good friends with William Lewis Moore, a white civil rights worker who became a martyr for the movement after he was shot and killed in the south during his solo Freedom March in 1963. When Moore was killed, Peck delivered the eulogy at his funeral, and then gave the opening speech on May 19, when several dozen activists continued the march from where Moore was shot down. After the walkers were arrested and taken to jail, Peck and others marched to the jail singing Freedom songs.

On August 2, 1963, Peck was one of 30 people arrested for performing a sit-down in the street, while protesting the discriminatory state policies for the construction of the Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. On October 20, he spoke about the racist policies in front of 700 demonstrators at a New York City rally. On August 28, 1963, Peck represented CORE at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He then traveled to Bowie, Maryland, to picket the discriminatory housing policies. On April 22, 1964, Peck was one of the leaders for CORE's campaign at the opening day of New York's World Fair, protesting the discriminatory policies held by most companies sponsoring the Fair. More than 300 demonstrators were arrested on the Fair's opening day, including Peck, James Farmer, Bayard Rustin, and Michael Harrington.

In March 1965, Peck represented CORE at the march from Selma to Montgomery. He spoke as a CORE representative that day. When Peck returned home after the march, he personally funded Martin Luther King's campaigns, especially his 1968 Poor People's Campaign. When Dr. King was assassinated in April 1968, Peck honored him by traveling to Memphis on April 8 to join 40,000 other demonstrators in marching in support of the Memphis Sanitation strike that Dr. King had supported prior to his death. After the Memphis March, he traveled to Atlanta for Dr. King's funeral, which concluded with 50,000 demonstrators marching over four miles. In May 1969, he joined Coretta King and Ralph Abernathy in Charleston, South Carolina, to support black nurses on strike.

In 1975, Gary Thomas Rowe Jr. testified that he was a paid FBI informant in the Klan, and that on May 14, 1961 the KKK had been given 15 to 20 minutes without interference by the police. Peck filed a lawsuit against the FBI in 1976, seeking $100,000 in damages. In 1983, he was awarded $25,000, and by this time was paralyzed on one side after a stroke.

James Peck continued civil rights activism into the 1970s, until his stroke. By 1985, he had moved into a nursing home in Minneapolis, where he died on July 12, 1993, at age 78.

No comments:

Post a Comment